Musicians, like other performers, often experience some degree of nervousness or anxiety about playing in a group or for an audience. Even acclaimed celebrities report feeling stage fright. This has led some artists to use or abuse alcohol and drugs to relieve tension. Fortunately, there are better ways to find the calm center that furthers creativity.

Meditation is easy to learn, but takes a lifetime of practice. There are many approaches and techniques, but in its most essential form, meditation is simply a way of paying attention to the present moment.

Being aware of the present moment is the core of spiritual practice and one of the highest forms of wisdom. It’s also an ongoing challenge. But for musicians the present moment is where music happens, so it’s important to learn how to be there.

Even if we weren’t assailed by the multiple stresses and stimuli of our busy lives, our minds would continue to chatter away about worries, regrets, plans and hopes. In order to be fully aware of the present moment, we need to quiet the “monkey chatter” within us. This constantly pulls us back to the past or draws us to the future with all the emotional turmoil both can entail.

Meditation can be done anywhere, any time and in any position. It is best to start in a quiet, pleasant, comfortable place. You’ll want to eliminate as many distractions from the environment as possible. Your mind will provide enough distractions of its own.

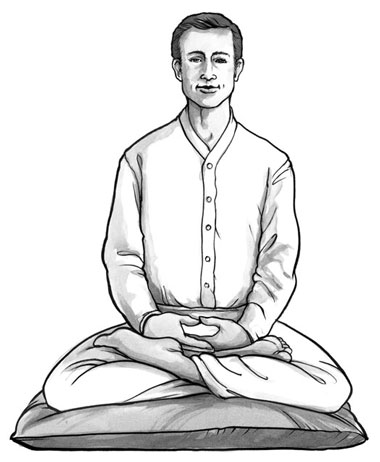

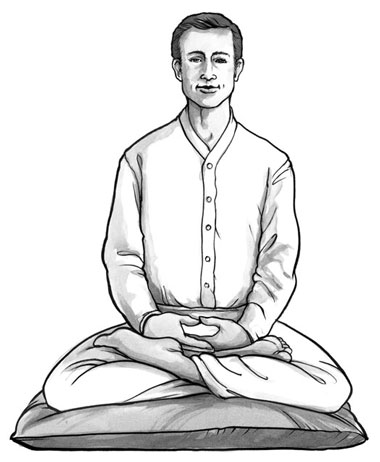

I’m most familiar with the Zen Buddhist form of sitting meditation, called zazen (“seated meditation”), which I began practicing in 1970. In zazen, you sit on the floor on a round cushion (zafu) in a full- or half-Lotus Position with your hands in your lap as shown below.

Full Lotus Position

In the Lotus Position [padmasana]—named for the shape of an open lotus flower, one sits cross-legged with the feet on the opposing thighs. The position is commonly used in Hindu Yoga and Buddhist meditation, but may be challenging for some. I can usually manage only the half-Lotus.

Since I’ve learned this approach, I find this position a helpful physical reinforcement of the practice. However, you can meditate just as effectively sitting in a chair with your feet flat on the floor (or even lying down, if necessary—provided you can stay awake).

It’s also best not to close your eyes; keep them lowered, but half open. Focus on a spot on the floor or some other neutral object. Some traditions focus on a spiritual object (flower, mandala, altar, statue of the Buddha, etc.). Your primary focus is elsewhere, so after a while you will almost stop seeing what’s in front of your eyes.

The essential element in any meditation practice is to pay attention to your breath as you inhale and exhale. This is both simple and challenging. As you try to focus on your breath, you will suddenly realize you’ve been thinking about an incident at the office, or what you need from the grocery store, what you forgot to tell your spouse or the paper you have to write.

Release yourself from any judgment or blame. (Meditation is in part an attempt to step outside the human ego.) Simply resume paying attention to your breath.

Thoughts will continue to intrude. Each thought is like a pebble or even a rock dropped into a pond. The water ripples and then gradually calms. As you continue to pay attention to your breath, your mind will calm. But don’t worry if another pebble drops in. Allow it to sink to the bottom and let go of it. Just pay attention to your breath again.

To focus on the breath, I have found it helpful to recite a gatha (“verse”) that the Vietnamese Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, proposed. This seems to sum up the essence of spiritual wisdom:

Breathing in I calm my body

Breathing out I smile.

Dwelling in the present moment,

I know this is a wonderful moment.

After reciting this to myself a few times as I inhale and exhale, I will sometimes shorten it to “in,” “out.” Another aid in focusing on the breath is to count from one to ten and then back down (I count it like music: 1 and, 2 and, etc., for the in and out breaths.). The persistence and insistence of the mind’s “monkey chatter” is such that I’ve never been able to complete a counting cycle before I got distracted and lost track. I simply begin again…and again…and again. No judgment, no blame, no regret.

Some traditions use a mantra to help focus the attention. This mantra may be given to one in secret by a guru or teacher (e.g., Transcendental Meditation). Perhaps the most widely used mantra is the Buddhist six-syllable Sanskrit mantra: Oṃ maṇi padme hūṃ. The text has been interpreted in various ways. I’ve often used it as the focus of meditation and the fact that it’s in Sanskrit helps me to focus.

While you can meditate almost anytime, it’s ideal to spend 20 minutes or so when you first get up in the morning.

Thich Nhat Hanh and others also encourage mindfulness breaks throughout the day when you bring your attention back to the present moment and notice your breathing. These may last a minute or longer depending on your situation. These are good times to recite the gatha above.

There are many books on meditation that can be helpful or supportive of your practice. I especially admire the work of Thich Nhat Hanh, who speaks from a Buddhist perspective, but to a Western audience. One doesn’t have to know or accept Buddhist teaching to benefit from his teaching on meditation.

Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center, has also written extensively about what he calls Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). While he was trained in Zen Buddhism, his concept of mindfulness is secular.

People become interested in practicing meditation for many reasons: to relieve or reduce stress and anxiety, to find peace, to relieve pain, to improve health, to connect more deeply with the universe. In recent years, scientific studies of meditation have established that it has measurable positive effects on the brain and the rest of the body. Meditation has been shown to improve immune function, lower blood pressure, reduce stress and increase empathy.

It can be helpful in developing your meditation practice to do so in a group of some kind. The support of others can make it easier to persevere when meditation seems frustrating or pointless.

And, ideally, if paradoxically, meditation is “pointless.” The more you are attached to a goal or goals for your meditation practice, the harder it will be to let go of the chatter, listen to your breath and pay attention to the present moment.

Further Reading

Benson, M.D., Herbert with William Proctor. Beyond the Relaxation Response. New York: Berkley Books, 1984 | 1985, 180 pp.

Hanh, Thich Nhat. Being Peace. Edited by Arnold Kotler. Berkeley, Calif.: Parallax Press, 1987, 117 pp.

Hanh, Thich Nhat. The Miracle of Mindfulness: A Manual on Meditation. Revised Edition. Boston: Beacon Press, 1976 | 1987, 140 pp.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, And Illness. New York: Delacorte Press, 1990; revised and updated edition: New York: Bantam, 2013, 720 pp.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. Mindfulness for Beginners: Reclaiming the Present Moment—and Your Life. Sounds True, Incorporated, 2011, 120 pp.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. Wherever You Go There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. New York: Hyperion, 1994, 279 pp.